Human Rights Day: Please Support The Calyx Institute's Work

A message and an appeal from Calyx's Executive Director, Nicholas Merrill

Human Rights Day

December 10, 2015

"No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence..."

-The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Now, for the first time in over eleven years - more than a quarter of my life - I can finally speak freely about my experience being conscripted into the FBI’s surveillance machine.

You may have seen coverage of the revelations in the news last week:

But before I dive into the topic of National Security Letters - one of the big lessons I have learned is that there are essentially three approaches to how we can grapple with the problem of our privacy rights being taken away.

1) Litigation in the courts. I have been working on that approach for a long time and I have learned a lot about procedural stalling, and how the system is unfairly stacked in favor of the government.

2) Legislative reform, despite that I was prevented from testifying before congress during the years of my gag order, my legal case resulted in some legislative reform anyway due to the publicity, but it the steps Congress has taken have been far less effective than I would have hoped. Which brings me to the third way:

3) Technical solutions to prevent the collection of communications content and metadata in the first place, and that is what we do at The Calyx Institute.

What Calyx Does

Calyx runs a significant portion of the Tor network. We run mostly Tor exit nodes, which are the most risky to run because that is where the Tor traffic appears to come from. This costs the organization a lot of money for the internet bandwidth, servers, and hosting bills. However it is important work that means a lot because we are helping people at risk to remain anonymous when accessing the Internet.

We also run an innovative Instant messaging service - currently servicing over 65,000 accounts - which you may have read about in The Intercept or if you use the ChatSecure client software on Android or Iphone, they default to using our server.

At calyx.net we provide free anonymized VPN access to anyone - for free - using the open-source LEAP project's software. We also will be providing free encrypted cloud-hosted email there as well when LEAP gets that part of its project working which should be very soon. But again, this will require funding to pay for the storage.

We have a number of other projects we would really love to have the time and resources to do more on including our work with DNSSEC and DANE, as well as our Encrypted Internet Exchange. But the organization has been chronically underfunded. Calyx is funded entirely by donations, with the occasional grant here and there. And that is why I would like to ask for your support.

Telling my story

It started on Tuesday, February 10, 2004. I was working as the president of Calyx Internet Access, a small Internet hosting and security business. That day, an FBI agent knocked on my door and handed me a National Security Letter. The letter demanded numerous categories of sensitive information about one of my clients and - like nearly all of the tens of thousands of National Security Letters, or NSLs, that the FBI issues unilaterally each year - the FBI forbade me from saying anything about it. I was gagged from disclosing the mere fact the letter existed, let alone its contents.

The moment I saw the letter, I knew something was terribly wrong. As a computer scientist, I knew that the categories of records the FBI was seeking to collect would violate individual privacy, freedom of speech, and freedom of association. As a communications service provider committed to user privacy, I was acutely aware of my ethical obligation to protect other peoples’ data. So I refused to hand over the data and fought for nearly seven years, with the help of the ACLU, to challenge the unconstitutional data demand and my gag order. The case resulted in landmark rulings finding aspects of the NSL regime unconstitutional. It also resulted in the Department of Justice's Inspector General being forced to audit the FBI's use of NSL's which proved massive abuse of the NSL powers. And it resulted in the NSL provision of the law being amended to ( insufficiently ) address some of the constitutional problems. But when the lawsuit ended in 2010, I still could not disclose what the FBI had commanded me to turn over. Now, in a case where I am represented by the Yale Media Freedom and Information Access Clinic, a federal district judge has ordered that I finally be permitted to speak without restraint.

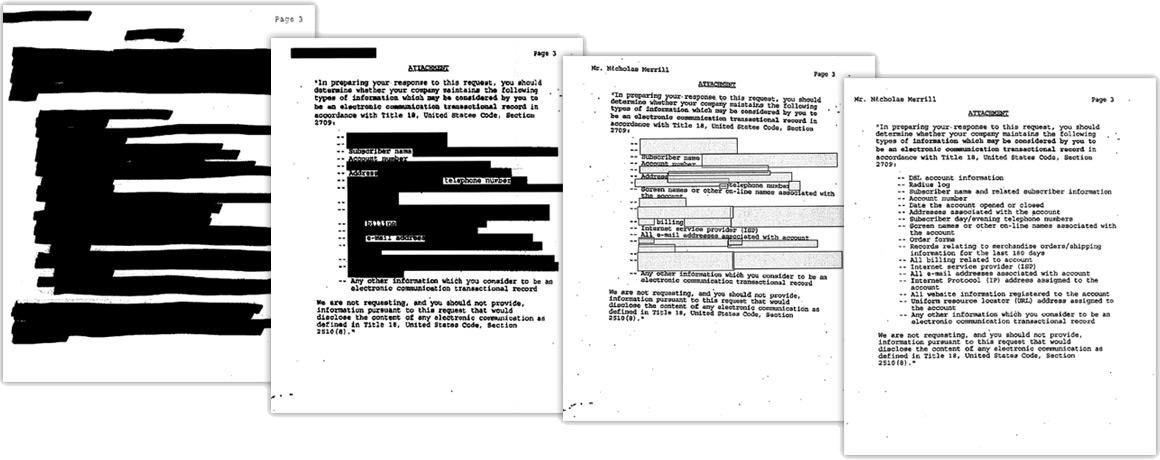

Over the course of the lawsuit, with win after win in court, we slowly chipped away at the restrictions on my speech, until the government finally gave up and stopped appealing. You can see a visual representation of the progression in this graphic of the attachment to the NSL below:

I can now reveal that the FBI believes it has the authority to demand a variety of sensitive information merely by issuing an NSL, without a warrant and without any prior judicial oversight at all. This information includes your entire web browsing history; your contact list - every person you correspond with via telephone, Skype, Facebook, instant messaging or email; and anything you have ever purchased online. Most alarmingly, the FBI believes it could use an NSL to monitor your physical location by collecting cell-site location information, which effectively turns your mobile phone into a location-tracking device.

That the FBI believes it can obtain - and has actually been collecting - this information just by issuing an NSL raise serious concerns about privacy and free speech. Because NSLs are so easy for the FBI to use and don’t require oversight by a judge, they have few safeguards against abuse. Indeed, we know that NSLs have been abused in the past. To compensate, Congress explicitly limited the FBI to collecting “non-content” metadata in the text of the NSL law.

But the secret list shows that the distinction between metadata and data is specious. Many privacy experts have explained over the past couple of years that metadata is actually much more revealing than communications content. Through automated mass dragnet surveillance of metadata from ISPs, mobile phone providers, EZ-Pass on or off tollways, and credit card transactions, the government can easily monitor the communications of and track the movements of The Tea Party, Associated Press reporters, or any other group or organization. Metadata can be used to track political opposition: who is meeting, where they are meeting and for how long. It can even reveal who is sleeping together by tracking the locations of mobile phones at night. Records of IP addresses can identify an otherwise anonymous individual communicating on the Internet, the other individuals with whom he or she communicates, and the websites or other online materials that an individual has accessed. In other words, if you try to speak anonymously on the Internet—a right protected by the First Amendment—the FBI can use your IP address to unmask you without even having to justify its actions to a court. This is precisely what the founding fathers wanted to prohibit when they crafted the 4th amendment.

It is especially troubling that the FBI believes it can use an NSL to collect cell-site location information, giving the Bureau the power to track your historical movements by plotting the location of your cell phone. Courts across the country have considered what safeguards the Fourth Amendment requires before the government can obtain exactly this information. Many have held that a full-blown warrant - or at least a court order - is required. But all the while, the FBI has secretly maintained that it can get the same records without going to court at all. In the course of my litigation against the FBI, the government said that it stopped collecting cell-site location information for the moment as a matter of policy, but it also could start doing so again without telling anyone.

Personally, what has been most challenging was being forced into an FBI scheme to keep this information secret from courts across the country, from Congress, and from the American people. I had to watch in silence as the public debated limits on the government’s ability to collect cell-cite location records, knowing full well that it was missing key information but unable to speak for fear of violating my gag. This summer, I had to watch in silence as Congress passed the USA FREEDOM Act restricting government access to this same material. Because nobody knew that the FBI felt it could get the information at the stroke of a pen if it so chose, the problem was left out of the legislative reform. I had to watch in silence. Until now.

I have written previously about how surreal and painful it was to live under a gag order that went on for far too long. But it is the American people who are harmed the most by FBI secrecy and the many thousands of NSL gag orders still in effect. At this moment in particular, with intelligence agencies again pressing for expanded surveillance powers, it is worth pausing to insist that we should know what powers they already have, how these powers are being used, and what happens to the data they collect. The public now knows some of what the FBI believed it could obtain just by issuing an NSL. What other surveillance authorities does the government claim in secret?